Report – CREATIVITY CONNECTS: TRENDS AND CONDITIONS AFFECTING U.S. ARTISTS

by CENTER FOR CULTURAL INNOVATION for

NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS

with additional support from Surdna Foundation and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation

September 2016

This report was produced through National Endowment for the Arts Cooperative Agreement DCA 2015-14 with the Center for Cultural Innovation. For the reader’s convenience, this publication contains information about outside organizations, including URLs. Inclusion of such information does not constitute an endorsement by the NEA.

Research Team and Contributors

The Center for Cultural Innovation assembled and coordinated the research team, which included Alexis Frasz, Marcelle Hinand, Angie Kim, Heather Peeler, Holly Sidford, and Marc Vogl. Marcelle Hinand served as project manager. Holly Sidford and Alexis Frasz of Helicon Collaborative wrote the report based on the team’s research. National Endowment for the Arts Chairman Jane Chu and staff members Winona Varnon, Laura Scanlan, Jason Schupbach, Laura Callanan, and Katryna Carter worked with the research team throughout the project and coordinated all aspects of the ten Regional Roundtables in concert with state arts agency partners. Sunil Iyengar, Patricia Moore Shaffer, and Bonnie Nichols offered editorial support and government statistics about artists.

Support provided by Surdna Foundation and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Bloomberg Philanthropies provided support for the Experts Convening.

About the National Endowment for the Arts

Established by Congress in 1965, the National Endowment for the Arts is an independent federal agency whose funding and support gives Americans the opportunity to participate in the arts, exercise their imaginations, and develop their creative capacities. Through partnerships with state arts agencies, local leaders, other federal agencies, and the philanthropic sector, the NEA supports arts learning, affirms and celebrates America’s rich and diverse cultural heritage, and extends its work to promote equal access to the arts in every community across America.

About the Center for Cultural Innovation

The Center for Cultural Innovation promotes knowledge sharing, networking, and financial independence for individual artists and creative entrepreneurs. CCI provides business training and grants; incubates innovative projects that create new knowledge, tools, and practices; and partners with investors, researchers, policymakers, and others to generate innovative solutions to the challenges facing artists.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

As the demographics of our country shift, the population of artists is growing and diversifying, as are norms about who is considered an artist by the arts sector and the general public. Artists are working in different ways—in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary contexts, as artists in non-arts settings, and as entrepreneurs in business and society. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census national data sets on artists have become more refined in the past decade, but arguably do not capture information on the full range of artists working today. Artists that may be omitted from these data sets include those who may not seek income from their work and those who use their artistry as part of another occupation. As the nature of artistic practice evolves, many of the existing systems that train and support artists are not keeping pace.

Artists are always influenced by larger socio-economic trends and respond to them in how they make their work and construct their lives. This research found four main trends influencing artists today:

1. Technology is profoundly altering the context and economics of artists’ work.

New technological tools and social media have influenced the landscape for creation, distribution, and financing of creative work. There are benefits for many artists, including lowered costs of creating and the ability to find collaborators and new markets. There are also significant new challenges, such as an increasingly crowded marketplace, copyright issues, and disruptions to traditional revenue models.

2. Artists share challenging economic conditions with other segments of the workforce.

Making a living as an artist has never been easy, but broader economic trends such as rising costs of living, greater income inequality, high levels of debt, and insufficient protections for “gig economy” workers are putting increasing pressure on artists’ livelihoods. Artists also face unique challenges in accessing and aggregating capital to propel their businesses and build sustainable lives.

3. Structural inequities in the artists’ ecosystem mirror those in society more broadly.

Race-, gender- and ability-based disparities that are pervasive in our society are equally prevalent in both the nonprofit and commercial arts sectors. Despite the increasing cultural and ethnic diversity of the country and the broadening array of cultural traditions being practiced at expert levels, the arts ecosystem continues to privilege a relatively narrow band of aesthetic approaches.

4. Training and funding systems are not keeping pace with artists’ evolving needs and opportunities.

Artist training and funding systems have not caught up to the hybrid and varied ways that artists are working today. Artist-training programs are not adequately teaching artists the non-arts skills they need to support their work (business practices, entrepreneurship, and marketing) nor how to effectively apply their creative skills in a range of contexts. Funding systems also lag in responding to the changing ways that artists are working today.

“We have an opportunity right now to really change how our culture values art, creativity, and artists themselves … We can do this by being an integral part of building new, more equitable and sustainable structures and systems that work for not only artists, but for lots of other people as well. To capture this opportunity, we need to look beyond small artist- specific solutions to systems-level problems, and engage in the bigger, more urgent questions of our time.” – Laura Zabel, Springboard for the Arts

Artists are responding to evolving conditions and developing new skills and ways to structure their work. There are also entities, both within the arts and beyond, that are working to address conditions for broader constituencies that share some of artists’ challenges, such as burdensome debt.

The six-part analytical framework of support for artists that the Urban Institute developed as part of its 2003 study, Investing in Creativity: A Study of the Support Structure for U.S. Artists, remains relevant and useful today. Artists still need training, information, markets, material supports, networks, and validation. While positive change has occurred in many of these areas, all of these important supports for artists’ work are still necessary areas of focus. However, the current research suggests that greater attention must be paid to larger structural issues and trends influencing the overall context in which artists live and work. Only by addressing the challenges facing artists at the systems level will we truly enable our growing and increasingly diverse population of artists to thrive and contribute fully to a creative and vibrant society.

Five main priorities for future work emerged from the research. Action in these areas could move conditions for artists in a positive direction:

1. Articulate and measure the benefits of artists and creative work to societal health and well-being.

2. Address artists’ income insecurity as part of larger workforce efforts.

3. Address artists’ debt and help build their assets.

4. Create 21st-century training systems.

5. Upgrade systems and structures that support artists.

Addressing these priorities requires aligning artists’ interests with those of other people facing similar challenges and collaborating with broader movements for social and economic change.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Purpose of the Study

As part of its 50th anniversary observation, the National Endowment for the Arts in 2015 launched Creativity Connects1, a multipronged effort to show how arts-based creativity intersects with and enriches other facets of life in the U.S. As part of the initiative, NEA partnered with the Center for Cultural Innovation (CCI), a leading artist support organization, to conduct this national study on current conditions for artists and the trends affecting their ability to create work and contribute to their communities. In addition, NEA piloted a new grant opportunity (Art Works: Creativity Connects) that supports partnerships between arts organizations and non-arts organizations, and developed an interactive web portal (to be launched in September 2016) that visualizes how the arts connect to the U.S. creative ecosystem.

Artists are a vital part of every community in the U.S., contributing in multiple ways to the quality of our daily lives and to our economic and social well-being. Artists create the works of music, poetry, theater, visual art, film, dance, architecture, and craft that help shape our perceptions of the world and connect us to our multiple heritages and common humanity. Artists’ work inspires new ways of thinking and adds beauty and meaning to everyday experience. Artists play critical roles as community leaders, giving shape to community identity and voice to community concerns and aspirations. Artists are inextricably linked to the broader cultural sector and to the creative industries, and they help propel other parts of the economy as well. Everywhere they work and in their various capacities—in cultural institutions, schools, community centers, and entrepreneurial enterprises; in public spaces, in virtual worlds, and in private studios; producing tangible objects and guiding creative processes—artists are critical to social, civic, and business innovation.

The goal of Creativity Connects: Trends and Conditions Affecting U.S. Artists was to examine current and evolving conditions for how artists live and work. The world has changed significantly over the past decade, in ways that have important impacts on artists and creative practice. New technology has altered all of our lives, and has affected how artistic work is created, accessed, and supported. Creativity and creative processes are increasingly valued by businesses, civic leaders, and the general public. The U.S. has rebounded from the recession, but the economy has fundamentally changed. Income inequality continues to grow, and more workers in other fields are now supporting themselves through the “gig economy,” a way that many artists have worked for a long time. The demographics of our country are shifting, with growing Latino and Asian-American communities, and expanding populations of new immigrants, multi- racial youth, and aging Baby Boomers. There is now no racial majority in two states and 22 U.S. cities, and the entire nation will move in this direction in the next 20 years. The range of aesthetic forms and cultural expressions has exploded, driven by an increasingly diverse population, the imaginations of young people, developments in technology, and other factors. The growing cultural diversity of our population also increases the urgency of addressing issues of equity, access, and representation in all sectors, the arts included.

These trends invite us to think in new ways about artists, the value of their work, and their relationship to communities.

Methodology

This research project builds on a 2003 report by the Urban Institute (UI), Investing in Creativity: A Study of the Support Structure for U.S. Artists2. The UI study was an unprecedented and comprehensive examination of the needs and interests of artists. Among other contributions, the UI study developed a conceptual framework for understanding the field of artists and identified six domains that affect artists’ ability to do their work: validation; demand/markets; material supports such as space, equipment, employment, and funding; training and professional development; community and networks; and information.

Over the past 13 years, the UI framework has informed funders, policymakers, artist support organizations, scholars, and others interested in the creative work of artists and how to enlarge their creative contributions at local, regional, and national levels. The UI study spurred numerous initiatives to build the support structure for artists, including Leveraging Investments in Creativity (2003-2013), United States Artists, Chicago Artists Resources, the Bay Area Fund for Artists Matching Commissions Program, and a variety of other programs across the country.

Creativity Connects used the UI report as a starting reference and explored major changes in conditions for artists since 2003. The study methodology included the following activities:

1. In-depth interviews with more than 65 people including artists, heads of leading arts schools, cultural institution leaders, artist service organization staff public and private sector funders, scholars, and others;

2. Ten Regional Roundtable discussions that brought together more than 250 people in different parts of the country, including artists, funders, arts entrepreneurs, service organization leaders and other cultural leaders, commercial designers, community development experts, and others;

3. A literature review of more than 300 research papers, conference proceedings, articles, books, and other relevant publications on artists and trends Affecting artists;

4. An online research blog, Creativz.us, which commissioned 18 essays on relevant topics by field leaders (copies of which can be found in Appendix 3), and solicited responses from the public through a social media campaign; and

5. A convening of 30 field experts with diverse perspectives to vet preliminary findings.

Through these various activities, the research team explored a set of key research questions:

• How have the conditions for artists changed over the past decade?

• Are the current structures of support keeping pace with what artists need to succeed in their life and work?

• How are artists adapting to changing conditions and how are support structures evolving to meet their needs?

• What will strengthen the ecosystem of support, better enabling artists and creative workers to generate artistic work, live sustainable lives and contribute to their communities?

The study sought information about artists working in and across multiple sectors and contexts, including those working in nonprofit, commercial, public, community- based, and informal arts settings, as well as those working within or in partnership with non-arts sectors.

__________________

1 “Creativity Connects”™ is used with permission from Crayola LLC.

2 Maria Rosario Jackson, et , Investing in Creativity: A Study of the Support Structure for U.S. Artists, Urban Institute, 2003.

TRENDS AMONG ARTISTS

PART 1: SHIFTS IN THE ARTIST POPULATION AND THE WAYS ARTISTS WORK

In looking at shifts in the artist population and the ways artists work over the past decade, four primary findings emerged:

- The population of artists is growing and diversifying, and norms about who is considered an artist are changing;

- Substantial numbers of artists now work in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary ways;

- Many artists are finding work as artists in non-arts contexts; and

- Artists are pursuing new opportunities to work entrepreneurially.

Diversifying

1. The population of artists is growing and diversifying, and norms about who is considered an artist are changing.

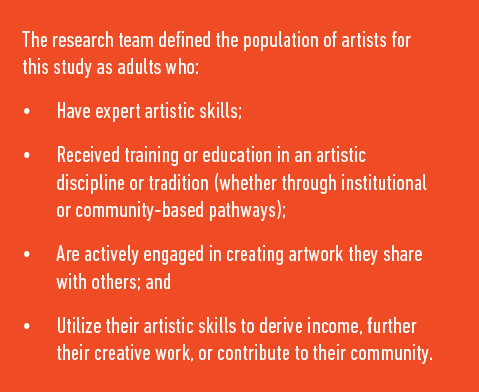

Although federal statistics can produce reliable counts of U.S. artists by a standard definition, there is a commonly held belief—among artists, cultural organizations, and some researchers—that the current categories are inadequate. Several factors thwart the ability to reach consensus, outside of federal data collection systems, about who should be considered an artist. For example, although artists are categorized as “professionals” in the U.S. occupational taxonomy, “artist” is not a designation owned exclusively by those with professional certification. There are no uniform standards that qualify artistic practice or use of the term “artist,” making it difficult to distinguish among different levels and kinds of artists.

Other complicating factors include:

- Social norms for what is considered artistic practice and artistic work changes over time, and official categories and designations may lag in capturing these evolving norms.

- The population of artists whose primary income derives from their arts practice includes many who do not have academic training in the arts.3

- Some people with degrees in the arts do not make all or even the majority of their living from their artwork. According to a 2015 survey of 140,000 graduates of arts and design schools conducted by the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP), for example, only half of arts graduates made over 60 percent of their income from their artistic practice alone. A 2003 Pew Research Center call study found that just 7 percent of artists earn all of their income from their art.4

“The definition of artist is elastic, and often hotly contested … Artists are stretched across many sectors, formal and informal, simultaneously and sequentially. Many are self-taught, despite formal educational opportunities offered to them. Their missions are…diverse and sometimes controversial. The fuzziness has some uses but when it comes to making the case for artists … it confuses.”

– Ann Markusen5

Federal data sets from the Current Population Survey (CPS) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the American Community Survey (ACS) by the U.S. Census suggest the following features about the U.S. artist community:

- In 2015, 2.3 million people had primary jobs as artists, working in one of BLS’s 11 categories6—an increase of about 185,000 between 2005 and 2015. This group represents approximately 1.5 percent of the labor force.7

- Approximately 271,000 workers who hold primary jobs in other sectors held second jobs as artists.8

- Artists are highly educated—59 percent of artists have bachelors’ degrees or higher, compared to 31 percent of U.S. workers overall.9

- The majority of working artists earn less than professionals with similar educational achievement in other fields.10

- Median incomes for fine artists, actors, musicians, dancers, choreographers, photographers, and “other entertainers” are below the median income of the U.S. labor force overall ($39,280).11

- Artists are 3.6 times more likely to be self- employed than other workers (34 percent vs. 9 percent).12

Refinements in the surveys conducted by CPS and ACS in recent years have improved understanding of artists’ employment and work patterns. However, a number of labor economists and arts field leaders believe the available federal data sources still undercount the number of artists who would fit the definition used by this study.13 This is because CPS and ACS figures may not be including practitioners who fall outside of the BLS categories—for example, culinary artists, social practice artists, or artists who work embedded within other sectors. The numbers also exclude large numbers of folk artists and tradition bearers who are expert in their artistic practice and whose artistry is important to the cultural or spiritual life of their communities, but who make most or all of their income in other professions.14 Official counts likely exclude many Native-American artists and Mardi Gras and carnival culture bearers, for example, as well as many community-based artists. Some cultural traditions discourage or even prohibit profiting from artistic work, and federal data on volunteering in the arts may not adequately capture the patterns for these kinds of professional artists.15

Data on personal creativity further complicates the picture. Multiple surveys confirm that making art is a fundamental part of life in the U.S., and the line between professional and amateur artist is blurry. Some studies suggest that as many as ten million adults receive at least some income from their artmaking.16 The proliferation of technological and social media tools—from iPhones to YouTube to 3D printing—is making it easier and less expensive for millions of people to make and distribute art. Some of this work reaches professional levels of quality, and some so-called “amateurs” are experiencing popular, critical, and financial recognition in professional spheres.

Interdisciplinary Work

2. Substantial numbers of artists now work in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary ways.

Cross-discipline collaboration in the arts has a long history but throughout the study, we heard repeatedly that increasing numbers of artists are working in hybrid ways that defy discipline classifications.17 For example, one-fifth of the 2,200 performing artists supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation from 2000- 2014 categorized themselves as multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary, and a Future of Music Coalition survey of more than 5,000 musicians in 2011 found that a similar percentage (22 percent) chose to write in a description of their music rather than select from a list of 32 musical genres.18 For many artists, the time and creative skills of multiple partners are required to bring their work to completion. Traditional ways of categorizing artists by discipline or providing grants to single individuals do not account for these kinds of practitioners, and this mismatch can have real consequences. Musicians or other kinds of artists whose work falls outside of genres listed on a grant application, for example, may find themselves ineligible for support.

Some artists are becoming proficient in multiple disciplines simultaneously—visual, performing, and other media—and bringing all that expertise together in a given work or series of projects. Others maintain focus in a primary discipline but pursue cross-discipline collaborations—choreographers working with filmmakers, for example, or musicians with visual artists. Art schools are reflecting and encouraging this interest by offering expanded interdisciplinary curricula. New technologies and the Internet are also important drivers of this artistic blending, enabling artists to see more work in multiple genres, experiment with mixing media and find creative partners outside of their existing networks.

Artists have long worked across nonprofit, commercial, and community sectors, as Ann Markusen’s 2006 report Crossover: How Artists Build Careers across Commercial, Nonprofit and Community Work demonstrated. Artists continue to do this kind of crossover work today, and some of the traditional distinctions between nonprofit, commercial, and community-based forms are dissolving. In particular, divisions between “high art” (traditionally the domain of the nonprofit sector) and “popular art” (traditionally the domain of the commercial sector) are becoming less apparent in the minds of creators and consumers. For example, accomplished playwrights, such as Tony Award-winning David Henry Hwang, are now engaged in scriptwriting for television. In this medium, they can tell different kinds of stories and reach different audiences using different creative tools (in addition to accessing new sources of revenue). Some dramatic television series are now recognized as leading innovators in artistry and storytelling. However, the structural divisions between different sectors, identified by Markusen in her report, remain barriers to artists’ ability to navigate and optimally integrate a hybrid career.

Non-arts Contexts

3. Many artists are finding work as artists in non-arts contexts.

Most professional artists work in fields related to their artistic interests and training, switching between adjacent industries rather than entering wholly unrelated domains of work. In the CPS dataset of artists who changed jobs between 2003 and 2013, for example, 59 percent ended up in one of five fields that have some connection to the arts or creativity.19 SNAAP surveys of arts graduates indicate that about two-thirds of respondents report their current jobs are “relevant” or “very relevant” to their academic training, which is on par with or higher than graduates from other fields.20

At the same time, increasing numbers of artists are working as artists in other settings, as more sectors are recognizing the value artists can add to their work. This includes schools and afterschool programs,21 community centers, hospitals and religious organizations, park systems, mayors’ offices, neuroscience labs, technology companies, senior centers, consulting businesses, veterans’ facilities, and a wide variety of other industries and locales.

As the UI study observed, and Ann Markusen’s work on crossover patterns in artists’ work confirms,22 many artists move between and among different work environments, often erasing the boundaries between them. Even artists in disciplines that have very formalized institutional structures—ballet dancers and symphonic musicians, for example—often work outside these structures as part of their practice. The contexts in which artists pursue their artistic work are increasingly fluid, shaped by artistic goals, training, resources, partners, location, and timing.

Multiple factors have contributed to many artists working across sectors and in non-arts contexts, including:

- The increasing urgency of socio-political issues— including economic and other forms of inequality, a troubled criminal justice system, and climate change—is spurring some artists to address these issues by working in non-arts settings.

- Leaders in a growing number of non-arts sectors— including community development, healthcare, transportation, technology, and public safety—are recognizing that artists’ creative skills and processes can assist their work.

- Limits on the ability the nonprofit and commercial arts sectors to fully employ all professional-level artists is propelling some artists to look elsewhere for work opportunities.

- A few illustrative examples of artists working in other sectors show just some of the range and variety of this kind of practice:

- Artists with Ideas XLab in Louisville, Kentucky, are working with insurance companies, governments, and communities to improve health outcomes in low- income communities.

- Visual artist Jenny Kendler is an artist-in-residence with the National Resources Defense Council, working on environmental projects with NRDC staff.

- McKinsey & Company is employing artists as part of its strategy consulting teams in diverse industries.

- New York City, Boston, Los Angeles, and many other municipalities are sponsoring artist-in-residence programs that embed artists in city departments, including in agencies such as the Department of Design and Construction, the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, the Department of Veterans Services, and the Housing Authority.

- In partnership with hospitals, veterans groups, and the U.S. military, artist Brian Doerries’ company Outside the Wire uses Sophocles plays to engage civilian and military audiences in discussions about the challenges faced by veterans, their families, and their communities.

Three movements are contributing to the growth in this cross-sector work in significant ways: creative placemaking, socially engaged art practice, and design thinking. All three have roots going back many years, but all are being increasingly formalized and supported now.

- Creative placemaking seeks to position the arts as a core component of community planning and development and integrate the arts into the social, physical, and economic fabric of communities.

- Socially engaged art encompasses a range of approaches and philosophies linked by the artist’s intention to have a social impact with the artistic work.

- Design thinking refers to the use of design methodologies and tools in problem-solving in businesses and industry contexts.

These movements are indicators of the rising visibility and status of the arts, and artists, in non-arts settings, but they are not without controversy:

- Creative placemaking has created a useful framework for engaging diverse community development sectors in new kinds of partnerships with the arts, and generated many new opportunities for artists to connect with other fields. However, in some places this approach has been criticized for accelerating displacement of long-term and lower-income residents (including artists) in strong real estate markets.

- Growing attention to “social practice” art in academic training and arts funding programs has increased the acceptance of socially engaged work within the nonprofit art world. However, these developments have also raised concerns about the appropriation and misapplication of methods that have deep roots in low-income communities and communities of color by people who are not from or based in these communities, and who may be insensitive to local concerns and dynamics. Critics believe that the increased attention for this work often privileges practitioners trained in art schools or who have access to arts philanthropy—rather than community-based artists, many of whom have been doing this work for decades without much funding or validation from the formal arts infrastructure.

- Design thinking is a significant trend in design and business schools, but relatively few artists (except designers and artists trained in these design thinking programs) have been able to translate their creative processes into this kind of service. Nathan Shedroff, the chair of the California College of the Arts’ MBA in Design Strategy, makes a distinction between “design thinking, design craft, and design process.” He suggests that there is something similar to this in the art world. “There are many types of artists and someone who is great at the craft of painting may not be great at applying those skills to a real world problem.” Within the arts, he notes, “we haven’t done a good enough job of articulating the different things artists can contribute to other sectors yet.”

Despite growing awareness of the value of cross-sector work, educational pathways are still not effectively equipping artists to work in non-arts contexts, nor are other sectors (urban planning, healthcare, or economic development, for example) fully preparing their professionals to understand how to effectively work with artists. Randy Swearer, the vice president of education at Autodesk and former dean of Parsons School of Design, notes that innovation-driven companies have “a deep and powerful need to integrate creative thinking and creative processes” into their work, and “the way that artists are able to frame and understand problems and develop interventions is of tremendous value.” However, efforts to date to integrate art and artists into disciplines like engineering and business at universities are lacking depth and nuance. On the arts side, as Swearer says, “the narrow media- and discipline-specific way studio artists are taught in fine arts schools inhibits their ability to take the lessons they are learning and apply them to other areas of the world. The identity that they take on in art school as ‘fine artist’ also limits how they see their role in the world.”

Recognizing the value artists can bring as thinkers, creators, and problem-solvers in other realms has great potential to benefit artists and society at large— by providing new pathways for income, validation, and connection to community needs. However, as this cross-sector work gains increased attention from funders, academics, policymakers, and others, the ethics of how (and by whom) this work is defined, performed, and supported will be critical to consider.

Entrepreneurship

4. Artists are pursuing new opportunities to work entrepreneurially.

The terms “entrepreneurship” and “social entrepreneurship” are now widely used, but their meaning varies according to user and context. For the purposes of this study, we draw from Howard Stevenson’s definition of entrepreneurship as work that pioneers a truly innovative product, devises a new business model, creates a better or cheaper version of an existing product, or targets an existing product to a new set of customers.23 Roger Martin and Sally Osberg’s definition of social entrepreneurship is also useful: situations in which entrepreneurship is applied to remedy an unjust condition for a certain population or society at large in a way that fundamentally shifts the system.24

More artists are working in entrepreneurial ways to create new and previously nonexistent opportunities for themselves, other artists, and their communities. Here we note just a few examples of successful entrepreneurial ventures created by artists that have created new markets for other artists:

- Actor Robert Redford founded the Sundance Institute in 1981 to support and create new markets for independent filmmakers. Sundance has vastly expanded the creative and business opportunities for a group of artists that previously had few outlets for their work.

- Rolling Rez Arts is a state-of-the-art mobile arts space designed to serve and ignite the creative economy on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, launched by the First Peoples Fund in 2015. It is a business training center and mobile bank that delivers training, arts programs, and retail and business banking services to artists and culture bearers on Pine Ridge.

- Artist Perry Chen, rock critic Yancey Strickler, and designer Charles Adler founded Kickstarter in 2009 as a crowdfunding platform for creative projects. At the time it started, it was a revolutionary way for artists to access funding and promote their projects.

- Artisanal furniture designer Bret MacFayden, in East Nashville, Tennessee, has created the Idea Hatchery, an arts-based small business incubator that provides artists with affordable retail space, a sense of community, and opportunities to market their enterprises collaboratively.

- OurGoods.org, co-founded by artists Carl Tashian, Louise Ma, Rich Watts, Jen Abrams, and Caroline Woolard in 2009, is a barter network that connects artists, designers, and activists to the trade skills, spaces, and objects they need to complete their creative projects.

Some artists have combined their art or design training with business degrees and produced spectacular results. According to John Maeda, former president of the Rhode Island School of Design and now design partner at the venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caulfiield Byers (himself a crossover designer-business technologist), a number of the most successful recent Internet start-ups, including AirBnB, were founded by what he calls “mutants”—people with deep expertise in both artmaking and business.25

Others artists are operating more like social entrepreneurs, seeking to address social or community problems with business interventions:

- BAYCAT in San Francisco’s Hunters Point, for example, is simultaneously tackling the lack of diversity in the fields of technology and digital media and addressing employment issues in its low-income neighborhood through training neighborhood youth in the digital arts, linking graduates with work opportunities in the tech field, and providing professional media production services to businesses.

- In rural Appalachia, the artist-run arts and media center, Appalshop, is partnering with Lafayette College to develop Mountain Tech Media (MTM), a national creative services and production company. This initiative employs local artists as part of a regional effort to build a new, creative enterprise-based economy for the Appalachian region.

- Conflict Kitchen is a Pittsburgh-based project by artists Jon Rubin and Dawn Weleski that serves takeout food based on the cuisine of countries with which the U.S. is currently in conflict. It serves as a beacon for people from these countries who are living in the U.S., and spurs crosscultural conversation and learning.

- Asian Arts Initiative in Philadelphia is leading a multi- year entrepreneurial effort to transform a neglected four-block alley on Pearl Street into a vibrant community cultural asset. Asian Arts has organized a series of interactive events to re-imagine and re-make the space, such as public design sessions, block parties, art installations, a Community Feast, and artist-in-residence projects. The work is connecting the diverse residents of the neighborhood, including the homeless shelter on one end of the block to luxury condominiums on the other end, as well as engaging artists, immigrants, and other community members in the area and beyond.

- Media artist/activist Esther Robinson has launched ArtBuilt Mobile Studios, which creates small mobile workspaces that enable artists, social-service providers, and micro-businesses to work in new ways and in new places. ArtBuilt collaborates with other artistic partners and community organizations in different neighborhoods to design and build mobile workspaces; advance the mobile workspace movement; and transform where and how artists, social service providers, and micro-businesses work today.

Across the country, there are hundreds of other examples of entrepreneurial endeavors led by artists.

Artists employ various business models for their entrepreneurial endeavors—nonprofit structures, barter systems and cooperatives, commercial models, for-benefit corporations, and fiscal sponsorships.26 Like many non-arts entrepreneurs, significant numbers of artists are self-employed. Self-employment offers the flexibility and autonomy that many artists need. According to the NEA’s “Artists and Art Workers in the United States” (based on data from the American Community Survey), approximately 34 percent of professional artists are self-employed, and they are 3.6 times more likely to be self-employed than others in the workforce.27 A recent report from the Center for an Urban Future found that, in New York City, the number of creative workers operating a side business outside of their primary employment jumped 61 percent—from 62,000 to 99,600—between 2003 and 2013.28

Just like non-arts entrepreneurs, artists’ intent may be more about social good or more about commercial profit, more about the community, or more about their own personal success. The most appropriate business structure will depend on what the artist is trying to achieve. One thing is clear, however: whereas 25 years ago, when there seemed to be just two primary pathways for an artist—the commercial arts or the nonprofit arts sector—now we see a much broader spectrum of options that include more artist- driven entrepreneurial endeavors. This fact further blurs the definitions of what an artist is, why they do their work, and where and how they deploy their talents.

__________________

3 In 2014, BFAMFAPhD, a collective of artists, designers, technologists, organizers, and educators, examined American Community Survey (ACS) data on working artists. The study found that when designers and architects are excluded from the sample, the majority of working artists do not have arts-related bachelors’ degrees (or higher). (Artists Report Back, BFAMFAPhD, 2014)

4 SNAAP Annual Report, 2015; and Mary Madden, Artists, Musicians and the Internet, Pew Research Center, 2004.

5 Ann Markusen, “Diversifying Support for Artists,” GIA Reader, Fall 2013.

6 The 11 BLS categories are: Actors; Announcers; Architects; Dancers and Choreographers; Designers; Fine Artists, Art Directors, and Animators; Musicians; Other Entertainers; Photographers; Producers and Directors; and Writers and Authors.

7 2015 Current Population Survey. The Current Population Survey is a monthly survey of 60,000 households that asks about employment status in the week prior to the survey. In 2000, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated there were 2.1 million artists in the U.S., up from approximately 700,000 in 1970. Between 1970 and 1990, there was a 20-year surge in the number of artists, a jump that surpassed the growth rate of U.S. workers overall. The growth rate for artists between 1990 and 2005 was the same rate as the overall labor force; Artists in the Workforce: 1990 to 2005, Research Report #48, National Endowment for the Arts, 2008; “Artists and Arts Workers in the United States,” Research Note #105, National Endowment for the Arts, October 2011.

8 Arts Data Profile #3, Keeping My Day Job: Identifying U.S. Workers Who Have Dual Careers as Artists, National Endowment for the Arts, 2014.

9 American Community Survey 2010-2014, PUMS. The American Community Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, gathers information about ancestry, educational attainment, income, language, employment, and other factors through monthly surveys of approximately 295,000 American households.

10 Ibid.

11 “Artists and Arts Workers,” National Endowment for the Arts, 2011.

12 American Community Survey 2010-2014, PUMS.

13 Throughout this paper we will use these official federal data sets to make points about artists’ income, health insurance status, and employment status. We recognize that this data may not include artists that fall outside official counts. Our overarching conclusions are drawn from the federal data as well as other sources of information— interviews, roundtables, and research literature—about conditions facing the diverse array of working artists in the U.S. today.

14 Ann Markusen and David King, The Artistic Dividend, University of Minnesota, 2003; Gregory H. Wassall and Neil O. Alper, “Occupational Characteristics of Artists: A Statistical Analysis,” Journal of Cultural Economics, 1985; “Artists Careers and Their Labor Markets,” Handbook of the Economics of Arts and Culture, Victor Gisburgh and David Throsby, editors, 2006; and others.

15 NEA’s most recent estimates show there were 7.3 million arts volunteers in 2012 (2.2 million who volunteered with arts organizations and 5.1 million who did arts-related volunteer work, e.g., performed art for non-arts organizations). NEA Guide to the U.S. Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account, 2013. Folklorist Amy Kitchener, of the Alliance for California Traditional Arts, estimates that there are as many as one million traditional artists in California alone. See also Paul DiMaggio and Patricia Fernandz-Kelly, Art in the Lives of Immigrant Communities in the United States, Princeton University, 2010.

16 Pew Research Center, Investing in Creativity. The National Endowment for the Arts’ How a Nation Engages with Art: Highlights from the 2012 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA) (2013) and other NEA data suggest at as many as 50 percent of U.S. adults personally engage in making art themselves.

17 Interdisciplinary approaches are increasing in other fields as well as more people recognize the limits of single-discipline or siloed approaches to complex problems. As Neri Oxman notes in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Design and Science from MIT, “Knowledge can no longer be ascribed to or produced within disciplinary boundaries but is entirely entangled.”

18 Holly Sidford and Alexis Frasz, Assessment of Intermediary Programs—Creation and Presentation of New Work, Helicon Collaborative for the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, 2014.

19 Joanna Woronkowicz, “Do Artists Have a Competitive Edge in the Gig Economy?” Creativz.us Essay, 2016. The five fields include independent artists, performing arts, spectator sports, and related industries; specialized design services; motion picture and video industries; other professional, scientific, and technical services; and architectural, engineering, and related fields.

20 SNAAP Annual Report, 2014.

21 Nick Rabkin, Teaching Artists and the Future of the Arts, 2012.

22 Ann Markusen, et. al., Crossover: How Artists Build Careers across Commercial, Nonprofit and Community Work, University of Minnesota, 2006.

23 Howard Stevenson is known as the godfather of entrepreneurial studies. Thomas R. Eisenmann, “Entrepreneurship: A Working Definition,” Harvard Business Review, January 2013.

24 Robert L. Martin and Sally Osberg, “Social Entrepreneurship: The Case for Definition,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Spring 2007.

25 John Maeda, TED Talk, October 9, 2012.

26 Artists using Fractured Atlas’ fiscal sponsorship program have raised more than $100 million for their projects since the program began in 2002.

27 “Artists and Arts Workers,” National Endowment for the Arts, 2011.

28 Adam Forman, et al., Creative New York, Center for an Urban Future, 2015.

TRENDS FACING ARTISTS

PART 2: TECHNOLOGY, ECONOMICS, EQUITY, AND TRAINING

Five specific issues were raised repeatedly as primary concerns for working artists—technology, economics, equity, training, and funding. These issues affect artists’ work today as well as their future options. These concerns interact with the shifts noted above, and they influence each other as well.

Technology

1. Technology is profoundly altering the context and economics of artists’ work.

New technologies and social media are changing all our lives and have particular impacts on the way that creative content is created and consumed. New technological tools are expanding the boundaries of artistic practice and the presence of art in daily life, as well as the ways people interact with and consume artistic products and creative content. Better and less expensive technological tools are influencing the way that many artists make work, and where and with whom they make it. These new mechanisms are fundamentally altering the cost structure and methods of creating, distributing, and consuming art, especially in fields with reproducible products such as music, writing, photography, and film. Online giving and crowdsourcing platforms are also changing the way some artists finance their work.

Impacts on Creating

Widespread access to inexpensive but highly sophisticated creation tools such as mobile phone cameras, music and video editing software, and graphic design programs is lowering barriers to creating high-quality work in technology-mediated disciplines. In some cases new technologies for creation, distribution, and financing have altered entire fields. For example, video games used to be very expensive to make and the risk of failure was high, so large production companies controlled what got made and only bet on potential mass market hits. Now, better and cheaper technology means that one or two creators can raise the capital they need through online platforms like Kickstarter and distribute their games through platforms like STEAM. This trend has led to an explosion in experimentation in content and form, and generated a more diverse range of creators and audiences.29

The ease of access to technological tools, and reduction of cost in using them, has also enabled artists to experiment with using traditionally consumer-oriented mediums for work that is more oriented toward artistic or social change purposes. For example, video artist Bill Viola collaborated with University of Southern California’s Game Innovation Lab to develop The Night Journey, a game that explores the topic of enlightenment.

New technologies, such as virtual reality and 3D printing, are triggering the creation of entirely new artistic specialties and they are spurring substantial growth in multimedia and cross-discipline productions. An increasing number of online platforms designed to facilitate creative collaborations, such as hitRECord and SoundCloud, reflect and propel artists’ growing appetite to collaborate artistically within and between disciplines. These mechanisms are being used in a range of ways. For example, the Disquiet Junto page on SoundCloud encourages experimental sound artists to post tracks in response to a compositional challenge and then exchange critiques. These tools facilitate artists’ ability to locate and work with artistic collaborators from around the world.

In addition, technology is enabling artists to collaborate with people in other fields to achieve mutual goals. Enspiral, an online collaboration started by freelance artists and designers and activists in New Zealand, now facilitates global collaborations focused on positive social impacts. Through this mechanism, artists are collaborating with lawyers, accountants, lay people, and others to organize, finance, and realize projects.

The critically acclaimed 2015 movie, Tangerine, is an example of how these various technologies can come together. Tangerine could not have been produced even five years ago: it is a transgender love story shot on an iPhone, edited with an $8 app, that involved cast members located through the online platform Vine, and used scoring found through SoundCloud. It was made with a budget of $100,000.

“Amateur” photographer Matt Black’s experience also illustrates how technology is making it possible for new people to enter fields that used to require expensive equipment, training, and professional networks. Black’s iPhone images of poverty in his rural hometown in Central Valley, California, were picked up and publicized by MSNBC after he posted them to Instagram. This led to his receiving the W. Eugene Smith Grant Award (the “Nobel Prize of journalism”) and a nomination to join Magnum, the world’s premier photo agency.30

There are many positive benefits of these developments but there are downsides to these trends as well. One negative consequence is that technology enables producers to engage less expensive talent in other parts of the world. Vijay Gupta, co-founder of the Street Symphony in Los Angeles and a first violin for the Los Angeles Symphony, notes that “work for classically trained musicians is dwindling” in the U.S., and “orchestra jobs in film are moving overseas because a composer in L.A. can conduct a less expensive orchestra in Singapore using Skype.” In fields like music and photography, business models have been completely disrupted by digital technology, which has driven down the prices for content and increased competition, making it ever harder for professionals in these fields to sustain careers.31

Impacts on Financing

New online platforms are creating new ways for artists to finance their work. Crowdfunding sites—Kickstarter and Indiegogo, for example—extend the possibilities for artists to find “commissioners” for specific projects from their extended networks and the general public. In 2015, Kickstarter reported that its users, a substantial majority of whom are artists, raised more than $125 million to support their projects.32 Patreon is another platform that uses a modern-day patronage model to enable artists to secure sustained, unrestricted support for their work through monthly contributions from fans and admirers. Revenues range, but some artists using Patreon receive as much as $7,000/month in contributions from hundreds of individual patrons.

In addition to helping artists raise money, there are emergent Internet-based platforms that show promise for helping artists to manage and gain more control over contracts, assets, revenue, and other forms of property without traditional middlemen. This is a benefit because existing corporate or nonprofit technology platforms tend to prioritize consumers over content providers (who are frequently artists), and often do not have good mechanisms to protect artists’ work or ensure they are paid fairly for its use. Ethereum, for example, uses blockchain technology to enable people to create markets, store registries of debt, move funds, and handle other functions. This technology is new, and it is not yet clear how it will be employed by artists, but pilot projects—such as Ujo Music and Ampliative Art—are experimenting with this technology to create platforms for sharing and creation that are more favorable to artists than the commercial ones that currently exist. Ujo Music, for example, is hoping to use “smart contracts” to ensure that musical artists receive revenue from use of their works in ways that current platforms like SoundCloud, Spotify, and YouTube are not set up to deliver.

Impacts on Distributing and Consuming

Social media and online platforms are changing the ways artists interact with audiences, communities, and stakeholders—and are replacing many traditional gatekeepers and intermediaries. Online platforms such as Facebook and Instagram allow an increasing number of artists to build a community around their work, while others like Artsy, Etsy, red clay, Behance, and CD Baby enable artists to go directly to the marketplace. Many of these sites have replaced live agents, producers, marketers, commercial gallerists, and other people who formerly played the intermediary role of connecting artists to audiences and consumers.

In some cases, these outlets are actually growing new markets for artwork. In 2014, for example, Etsy reported that 1.6 million artists were selling on its platform, offering 35 million items, and attracting 24 million buyers.33 The European Fine Art Foundation, which covers the international visual art market, reports that online sales of visual art nearly doubled between 2013 and 2015. A third of these buyers spent less than $1,500 and many were new to the art market entirely. Online platforms are especially popular with younger people: over half of art buyers between 18 and 35 report buying art online.34

Technology and social media have also altered people’s expectations of where, when, and how artistic experiences will happen, and increased people’s desire for both passive and participatory options. Platforms like YouTube (now posting more than 60 hours of video every hour, watched by more than 800 million unique viewers each month) and Instagram have vastly increased the amount of creative content available, much of it user-generated. This on-demand content has made the landscape more competitive for professional artists and producers/ presenters of all kinds. The marketplace is far more crowded and it is more difficult to get recognition. These platforms have expanded artists’ opportunities to interact with audiences, but also forced many to rethink or adjust their offerings. In interesting ways, these tools have shifted—or inverted—the relationship between creator and consumer, making the roles more fluid and interchangeable. This further contributes to the blurring of definitions about who is an artist today.

Challenges

While there are many positive benefits of new technologies and social media for artists, there are challenges as well:

- Artists are now increasingly responsible for being their own producers, and the vast majority must now manage the range of production, marketing, distribution, and fundraising functions once handled by agents, managers, and marketers. Technology and social media may reduce financial costs, but they require substantial time to learn and utilize effectively, and artists may face an opportunity cost if they do not participate in the new online systems with skill.

- Technology tools and distribution platforms, in general, benefit artists working in media-based art forms like film, recorded music, photography, and publishing more than live mediums like dance, theater, spoken word, and craft. The proliferation of technologically mediated content competes with live activities for audience attention. Also, since live art forms are usually more expensive from a consumer perspective, artists may be forced to reduce fees for live work in order to meet consumer expectations of value.35

- The availability of vast amounts of digital content has undermined the traditional compensation structures of fields with reproducible products—music, photography, literature, and journalism, most notably. It has also generated new challenges to intellectual property rights for artists who work in these realms. While artists may benefit from digital platforms that facilitate their access to audiences, these platforms are typically designed with consumers, rather than artists, in mind as the primary users.36 As a result, they prioritize providing content at low cost and often do not pay artists well or allow them to determine how their work will be used. For fields like journalism and photography, the proliferation of easily accessible and high quality “amateur” content means it is a buyer’s market, making it almost impossible to earn a living wage selling work.

- Artists with access to technology and who have large networks of associates with substantial discretionary income are the most likely to benefit from crowdsourcing platforms. Artists in lower economic brackets, those who lack high-speed broadband access and/or those who have more limited social networks have less success with these mechanisms. Crowdfunding tools tend to reproduce existing socio- economic inequities and funding patterns in both the nonprofit and commercial art worlds. Money goes to artists with more established reputations who are located in major cities, reinforcing the lack of diversity and distribution patterns in the arts more generally.37

Crowdfunding has spurred a board game revolution, but will it spur a revolution in dance as well? Digital platforms like Kickstarter are touted as great equalizers that let the ‘little guy’ find success independently, but the sorting forces of better matchmaking can also further isolate the little guys. In a world where things ‘go viral’ and ‘trend,’ there are power laws at work that can accentuate the sorting into winner and losers. Digital platforms like Kickstarter may be better as ‘pre-sale’ retail platforms than ‘venture capital for the masses.’”

— Douglas Noonan, Indiana University

- Crowdfunding tends to favor defined near-term projects or products rather than longer arcs of work or process-oriented endeavors.

- Younger generations of artists have greater facility with new technologies and can make faster and easier use of these tools. Less tech-savvy artists (including many over 50) who do not have the training, tools, or inclination to adopt these new creation and distribution systems are seriously disadvantaged, as are people in many rural or low-income areas that do not have access to the Internet.

- Platforms like Twitter and YouTube give the illusion of neutrality because anyone can upload content, but many of the old systems of gatekeeping and power distribution have migrated into the new technological world. Although there are occasional surprise viral hits, corporations continue to exert control over most of what gets seen, distributed, promoted, and shared at scale. While companies like Amazon, Spotify, and Netflix benefit from the “long tail” of products finding niche audiences, these sales do not provide a living wage for the artists themselves.38

For more on this theme, see Creativz.us essays in the Appendix.

“Technology Isn’t Magic. Let’s Make it Work Better for Artists and Musicians,” by Kevin Erickson and Jean Cook

“For Profit or Not, Artists Need Tech Designed for Artists,” by Adam Huttler

“Why Video Games and Funders Don’t Click, and How to Fix It,” by Asi Burak

Economics

2. Artists share challenging economic conditions with other segments of the workforce.

Throughout the study, we heard reports on the challenges of making a living as an artist, whether in the nonprofit or the commercial sector or a combination of both. The artists’ world is competitive, adequate reliable employment is elusive, and philanthropic interventions— gifts, grants, and awards—are modest and irregular. Chronically low wages in much of the nonprofit sector is a challenge for many artists, and many cultural institutions expect artists to work for free or for nominal fees. One person spoke to a sentiment shared by many in saying, “There are no standards for employment contracts in many areas of the field, and too many cultural groups rely on artists to discount their labor in order to survive themselves.” The expectation that artists will subsidize the work has many consequences, including diminishing the ability of many artists to work in the sector at all— especially artists without other sources of financial support.

Technology has opened new opportunities for many, but the vast majority of artists who earn their primary income from the arts still earn less than $39,280/year, which is not a living wage in many cities with high concentrations of artists.39 A significant number hold multiple jobs to make their income.40 This overall pattern has not shifted substantially in the past decade.

What has changed is the larger context in which artists are working and living:

- Income inequality is growing, and the cost of living is increasingly difficult for people in the middle and lower income ranks.41

- Median rents are rising. In many major cities, rents exceed $2,000/month, pricing many artists out of these communities.42 While more than a third of artists live in metro areas with populations of more than five million, a growing number are choosing to work in “peripheral cities,” small towns or more rural areas.43

- Similar real estate pressures on small and mid- sized arts organizations in both the nonprofit and commercial sectors means these organizations face displacement or diminished capacity, undercutting critical opportunities for artists to rehearse, convene, and present work to audiences.44 In some places, this reality has pitted the interests of artists and arts organizations against each other.

- While the Affordable Care Act has helped many more artists access health insurance, premiums are still challenging or completely out of reach for large numbers. BLS data from 2016 suggests, for example, that 80 percent of all artists in the 11 occupations that it tracks have private insurance, but coverage varies widely by field. For example, only 49 percent of dancers and choreographers reported that they had insurance.45 In a Future of Music Coalition survey in 2013, only 57 percent of respondents indicated they had health insurance (at a time when 83 percent of the general population did).46

- Artists’ debt burdens are escalating, consistent with trends for the general population. A 2014 survey by the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP) found that 66 percent of recent art school graduates are carrying substantial debt, including 33 percent who have loans between $30,000 and $60,000.47 This financial weight has direct impacts on artists’ choices about career, family, and advanced education.48

Artists are also affected by larger trends in the labor market, notably the rise of contracted workers and the “gig economy.” The “gig” terminology derives originally from the performing arts, and refers to the lack of an ongoing contractual relationship with a single employer—a condition that has long defined the lives of most musicians, actors, dancers, and others. Many other people are now working in this way, either by choice, necessity, or both.

As part-time or contingent workers, artists usually do not receive health insurance, retirement, family leave, workmen’s compensation, and other benefits and protections that full-time employees receive. This fact also means they may struggle to build assets and capital, which can provide a buffer against variable or unpredictable wages and income.49 A substantial number of artists were working gigs long before the concept became mainstream, but there is now growing awareness of the stress and negative consequences of trying to survive on part-time, short-term, and low-wage jobs without adequate worker protections. As growing numbers of workers become part of the gig economy, there are more opportunities for artists to find common cause with others in advocating for attention to these issues. For example, Strike Debt and Rolling Jubilee are initiatives using multiple methods—including art and creative activism—in their efforts to abolish debt. Debtfair is a network of visual artists whose work online and in live exhibitions explores the debt burden behind inequality in the art market.

In addition, artist entrepreneurs face many challenges that other sole proprietors and small business owners do not. Often artists do not see themselves as aligned with other non-arts business owners, even when they face similar challenges and have similar needs. As a result, they may not take advantage of available services, such as programs offered by the Small Business Administration or similar entities. In addition, lending and other financial services available to conventional small businesses may not accommodate the distinctive needs of artists and their businesses. Artists’ unconventional income histories, their lack of familiarity with financial terminology and processes, and the fact that many lenders/investors do not understand the value proposition of their work are all impediments to artists’ ability to secure adequate financing.

Diminished Tolerance for Risk

This economic situation has other, indirect effects on artists’ opportunities and work, as rising costs of business and an increasingly competitive marketplace diminish the tolerance for risk among producers and presenters (in both nonprofit and commercial spheres). This trend pushes many artists to do more conservative and commercially viable work. The for-profit and nonprofit sectors are reinforcing a winner-take-all phenomenon— increasingly backing a relative few “art stars” and “hits” and disregarding hundreds of thousands of others.50

This more conservative perspective on risk appears to be affecting philanthropic behavior as well. Artists who seek support from foundations and nonprofit funding intermediaries report that there is less interest in experimentation and open-ended artistic exploration, and little interest in kinds of work—such as community- based cultural projects—which may take many years to fully realize. Increasingly, funding entities and presenters of all kinds seek measurable outcomes and reliable results, and focus on specific projects rather than investing in the long-term development of an artist’s ideas and body of work. In many interviews and every Regional Roundtable, we heard that these trends discourage artistic exploration and the long-term development of artistic ideas, and do not take into account the fact that intermediate “failures” are essential to artistic innovation and long-term success.

Responses

Artists and others are working intentionally to address many of these economic issues. Coalitions of artists are organizing and campaigning for fair compensation for artists through organizations like W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) and the Freelancers Union. In addition, artists are finding new ways to share resources, not only in creating work but also in managing business and organizational functions. The number of artists’ collaboratives is increasing, many of which provide artists with shared back-office functions— online and off Co-located office spaces such as the Center for New Music in San Francisco, for example, and ArtsPool (an online cooperative bookkeeping and financial management service), and hundreds of maker spaces and cooperatives around the country reflect artists’ growing interest in finding cooperative ways to respond to shared needs.51 Many artists are using fiscal agents rather than starting their own 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations or commercial entities, and some of these programs provide back-end organizational services as well. For example, Fractured Atlas, the largest arts- based fiscal sponsor in the U.S., has been the umbrella for close to 10,000 individual artists’ projects over the past five years and also provides insurance, ticketing software, and visa assistance.

There are hopeful signs that more banks, community development corporations, community development financial institutions (CDFIs), and other entities are addressing the challenges artists face in accessing space, capital, and financial services.

- The Community Arts Stabilization Trust (CAST) and the Minnesota Street Project in San Francisco, Spaceworks in New York City, and Artspace Projects, Inc. in more than 30 communities across the country are helping to develop affordable work and living spaces for artists.

- The Maryland Institute College of the Arts is working to help the Small Business Association in Baltimore to adapt its services to better suit the needs of artists.

- The Union Bank & Trust’s Catalyst Initiative in Omaha, Nebraska, is developing creative ways to make loans to artists and assist them in managing both personal and work-related finances.

- Northeast Shores Development Corporation, in Cleveland, Ohio, has pioneered new approaches to help artists with home ownership.

- The Surdna and Kresge Foundations have partnered to fund seven CDFIs around the country to provide training to artists and creative entrepreneurs that enables them to develop business strategies, connect their work to markets, and secure financing to jumpstart or grow their businesses.

For more on this theme, see Creativz.us essays in the Appendix.

“What Artists Actually Need is an Economy that Works for Everyone,” by Laura Zabel

“What Does It Mean to Sustain a Career in the Gig Economy?” by Steven J. Tepper

“Do Artists Have a Competitive Edge in the Gig Economy?” by Joanna Woronkowicz

“Health Insurance is Still a Work-in-Progress for Artists and Performers,” by Renata Marinaro

“Artists, the Original Gig Economy Workers, Have More Rights than They Think,” by Sarah Howes

Equity

3. Structural inequities in the artists’ ecosystem mirror those in society more broadly.

Conditions for artists reflect conditions in the society at large, and the race-, gender-, and ability-based disparities that are pervasive in our society are equally prevalent in both the nonprofit and commercial arts sectors. As Carlton Turner of Alternate ROOTS puts it, “We continue to struggle with issues of inclusion, diversity, and equity in the arts and culture sector because our society continues to struggle with them.”

Despite the increasing cultural and ethnic diversity of the country and the broadening array of cultural traditions being practiced at expert levels, we heard repeatedly in interviews and Regional Roundtables that arts funding and presentation systems continue to privilege a relatively narrow band of aesthetic approaches, mostly based in the Western European fine arts. This is true for individual artists and their work, as well as the organizations that employ them and present their work. A sampling of data from a variety of sources reinforces the point:

- Artists able to make their full income from the arts are less socio-economically and demographically diverse than the total U.S. workforce.52

- Only 13 percent of writers and authors are non- White and/or Hispanic compared with 32 percent of the total workforce, for example.53

- Only 20.7 percent of designers and only 17 percent of fine artists are non-White and/or Hispanic.54

- 4.4 percent of arts school graduates are African-American (compared to 12 percent of the population) and 6 percent are Hispanic (compared to 17 percent of the population).55

- Approximately 4 percent of arts-related foundation funding is directed to organizations whose missions are dedicated to serving communities of color, including those based in African-, Arab-, Asian-, Latin-, or Native-American heritage.56

- Even less foundation arts funding is allocated to serve rural communities, or intended specifically to assist the work of folk artists and tradition bearers in indigenous communities.57

- Just 12 percent of the playwrights whose work was produced by nonprofit regional theaters between 2011 and 2014 were people of color.58

- Less than 5 percent of musicians in the nation’s symphony orchestras are African-American or Latino.59

- Out of top 100 films in 2014, less than 16 percent of directors, writers, and producers were women.60

- Only 32 percent of artists shown in New York and Los Angeles galleries in 2013 were women.61 Between 2007 and 2014, fewer than 25 percent of the solo exhibitions at five major art museums featured women artists.62

- One in four people in the U.S. still does not have Internet at home, which means that the lower costs of arts production and distribution offered by technology has not benefited artists equally, and may have actually increased disparities for the artists in low-income or rural communities who lack access to these tools.

This situation not only means a lack of equal opportunity for large segments of the artists’ population, it also means that our nonprofit and commercial cultural ecosystems do not reflect the pluralism of our country’s population overall. Artists reside in every community in the country, expressing a wide variety of cultural and aesthetic traditions, but the formal systems and structures of validation and support in the arts do not yet fully reflect this reality.

In our interviews and in the Regional Roundtables, several initiatives were mentioned as encouraging examples of leaders addressing the structural roots of these inequities.

- The Enrich Chicago initiative, for example, is working to increase support for culturally diverse groups and artists, and to place more young artists of color in paying internships;

- Grantmakers in the Arts’ has made racial equity a major focus of its work;

- the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs’ recently completed a survey on the diversity of staff and boards in cultural institutions and is launching initiatives in response to the findings;

- the Intercultural Leadership Institute—a partnership of the National Alliance of Latino Arts and Culture, Alternate ROOTS, First Peoples Fund, and Pa’i Foundation—was launched in 2015 to achieve cultural equity based on an ethics of difference, inclusion, and empowerment, addressing the need for culturally relevant and equitable practices in arts management and leadership;

- and Americans for the Arts has recently published a policy statement on cultural equity.

Many we interviewed applauded United States Artists for the notable diversity of its fellows roster over its ten-year history, and the commitment to inclusiveness in its selection processes that has produced this result. However, most people we spoke with believe that much more must be done if the organizations and mechanisms that support our creative ecosystem are to truly reflect and nurture the diversity of American artistry and cultural practice

For more on this theme, see Creativz.us essays in the Appendix.

“Why We Can’t Achieve Equity by Copying Those in Power,” by Carlton Turner

“Does Crowdfunding Change the Picture for Artists?” by Douglas Noonan

“Who Sets the Agenda for America’s New Urban Core?” by Umberto Crenca

Training

4. Training is not keeping pace with artists’ evolving needs and opportunities.

Appetite for professional training in the arts remains strong—approximately 120,000 people graduate with art degrees every year.63 Many more people make their way into art careers without academic training, through apprenticeships or other kinds of pre- professional education. Regardless of the entry point, the skills required to succeed as an artist today are not limited to mastering an art form or presentation technique. Increasingly, artists also need knowledge and skills in multiple areas of production, business, and social media, and must master the complexities and ambiguities of both making art and making a career in a contemporary world.

“We are at an important evolutionary moment, a millennial moment, in which the value we ascribe to artists and the roles they play in our communities needs significant recalibration, as do the ways we train artists and support their work.”

— Samuel Hoi, Maryland Institute College of Art

As more artists work in non-arts contexts, by choice or necessity, they also need heightened ability to improvise, collaborate, and transverse disparate domains.64 This requires that artists and educators think more about the distinctive creative capacities that are rooted in arts practice, and articulate those skills in ways that can be understood by people outside of the arts. We heard repeatedly that relatively few artists have been able to take advantage of the growing interest in creativity and design-thinking in the business and public sectors, for example, in large measure because they have been unable to articulate the value of what they bring to non-arts contexts.65 A continuing aversion to “instrumentalizing” the arts in for artists who wish to use their skills in non-arts contexts.

“Artists’ distinctive competencies include dealing with ambiguity, generating ideas, improvisation and

prototyping, reasoning with analogy and metaphor, and telling compelling stories in multiple mediums. These things can be useful capacities for many fields.”

— Steven J. Tepper, Arizona State University

In our interviews, Regional Roundtable discussions, and other research, people reinforced the point that artists are inadequately prepared for the contemporary world of work—inside or outside of the creative sectors. In both academic settings and more community-based or experiential training programs, young artists are not being educated in business or marketing skills, in strategic use of social media to advance their work, or in thinking about their entrepreneurial options. In a 2015 SNAAP national survey of recent art school graduates, 75 percent said they needed entrepreneurial and business skills in their art careers, but only 25 percent had received this training while in school.66 Less is known about training provided by apprenticeship or community-based programs.