Debt: A System Failure, not an Individual One

The recently released report Creativity Connects: Trends and Conditions Affecting U.S. Artists found that debt—student debt, medical debt, credit card debt—is one of the most important factors influencing artists’ ability to sustain their lives and careers. Two thirds of recent art school graduates are carrying substantial student debt alone, which affects all of their choices and possibilities down the line and disproportionately affects people of color. The report argues that, with regard to debt and many other issues, artists share common cause with other people and must join forces with them to achieve systemic change. To this end, we are excited to share this essay from Hannah Appel, a leading thinker and organizer working to disrupt our current system of debt through creative activism. She says, “when crippling debt becomes the norm, it points to a systemic problem, not a personal one.” What possibilities might there be for artists to contribute their numbers and creative juices to disrupting a broken system and reinventing it so it is fairer and works better for all? And how might artists benefit from joining forces with this larger movement for change? – Alexis Frasz, Editor

The last four decades of stagnant wages, tax revolt and crumbling social services, partially masked by “democratized” access to credit, has forced people to debt-finance college, health care, and housing. Meanwhile, the “creditor class” has reaped enormous rewards from this system. The rise of finance capitalism, in other words, has led directly to the rise of deep and protracted indebtedness in the vast majority of U.S. households. A few illustrative statistics:

- 77.5% of U.S. households hold consumer debt.

- Of indebted households, 40% use credit cards to cover basic living costs including rent, food, and utilities.

- 62% of personal bankruptcies in the U.S. are linked to illness and health care costs.

- The wealth gap splits along racial lines: In the wake of the mortgage crisis in 2008, African American families lost 50% of their collective wealth and Latino families lost 67%. White families, by comparison, saw their household wealth decline by 16% and recover much faster in the post recession period.

- In households that do not use formal banking services, 10% of families’ annual income goes to the fringe lending landscape – check cashing; rent-to-own finance; auto title lending; refund anticipation loans; pawnshops; prepaid credit cards and payday loans. The typical annual percentage rates of these services are much higher than banking services, ranging from 390 – 550%.

- According to a 2013 Federal Reserve report, student debt tripled between 2004 and 2012, and stands today at 1.3 trillion dollars. In 2015 U.S. students graduated from college with an average of $35,000 in debt, and defaults on student debt are now occurring at the rate of one million per year.

All of these situations negatively impact people’s credit scores, which then reproduces cycles of debt and compounds inequality. People with lower credit scores pay higher interest rates, have a harder time finding places to live, and in many cases are denied opportunities for work.

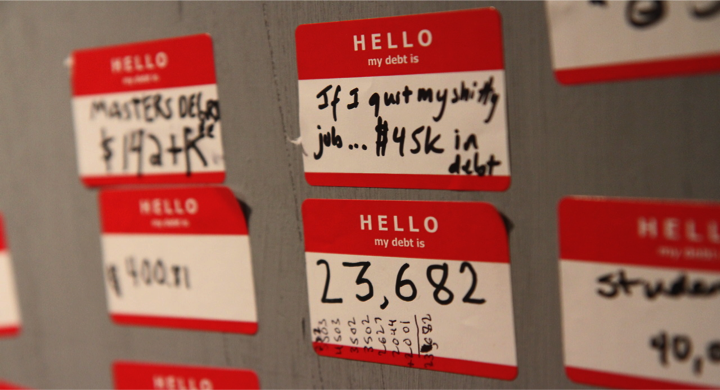

Experienced alone, debt is isolating, frightening, and morally laden with shame and guilt. But when crippling debt becomes the norm, it points to a systemic problem, not a personal one. To begin to address this problem we formed the Debt Collective, a union of debtors and their allies, who are attempting to harness our collective power to disrupt this unjust system. As oil tycoon JP Getty famously quipped, “If you owe the bank $100 that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that’s the bank’s problem.” The students who hold the 1.3 trillion dollars of education debt can, arguably, be the banks’ problem. The Debt Collective’s provocation is: can we reframe debt from an individual issue that causes isolation and shame to a platform for mobilizing collective action?

The hundreds of debtors who contact the Debt Collective each have a story of seemingly exceptional exploitation and pathos.

Chemotherapy treatment made mortgage payments impossible, and the house was foreclosed as I lay sick in bed.

My student loan debt ballooned as I worked an unpaid internship and a part time minimum wage job, and I’m unable to pay off even the compounding interest.

My wages were garnished for unpaid court fines, and now I can’t pay child support and I’m afraid I’m going to go to jail.

In aggregate, it becomes obvious that these stories are not exceptional but ordinary. Yet when debt stays private it remains shameful and isolating, and seems to signify an individual failure rather than the systemic and widely shared conditions of contemporary capitalism. One of the first tasks in organizing debtors, therefore, is to disrupt the ways people think about debt so that they feel empowered to act disruptively. While debt collectors hound the majority of us—and our credit scores plummet, we are denied rentals, jobs, or loans, our wages are garnished, our houses taken, or we are even jailed—bankers expect to have their debts forgiven, and are bailed out time and again. In other words, as individuals we experience debt as a moral failing, while banks make debt what it is – a political issue subject to negotiation and rupture. We must do the same.

To that end, the Debt Collective launched the Rolling Jubilee “a bailout by the people for the people” in 2012. Defaulted debt – unpaid medical bills, for example – gets sold to debt collectors on secondary markets for mere pennies on the dollar. So a $1,000 unpaid medical bill might be sold by a hospital to a debt collector for a mere $200. Debt collectors make their profit by trying to collect on the full amount. If I, the medical debtor, end up paying the debt collector the full $1,000, in addition to penalties and late fees, which most people do, that collector will have just made more than $800, or a 300% profit. For Rolling Jubilee, we got certified as a debt collecting agency and then crowd-sourced money to buy defaulted medical debt in these secondary markets. But instead of harassing individuals to collect it, we abolished it. To date we have bought and abolished nearly $32 million of medical and student loan debt, and we have debt buys in other categories up our sleeve.*

Rolling Jubilee provides relief to a handful of those struggling with medical debt or private student loan debt, but our political end game is not to crowd-source away everyone’s debt. Rather, the Rolling Jubilee is a spectacle that begins to draw attention to the ways debt circulates and re-circulates in widening gyres of accumulation by dispossession—creditors reap ever greater profits from debtors in part because most people don’t know how distressed debt markets work.

By showing people that the market value of their debt fluctuates radically, and can plummet to 2% of its value, the Rolling Jubilee also begins to call into question the sanctity of the contract itself. Debtors often imagine our debts as personal relationship between debtor and creditor: the creditor lent to me, and I am contractually and morally obligated to repay them. However, unlike lending to a neighbor or a friend, these forms of debt are not intimate relationships between debtor and creditor, but rather circulating relationships with negotiable, political terms, as the medical debt example above illustrates.

The Rolling Jubilee was simply one tactic—an attempt to change assumptions about what debt is and begin to shift imaginations of what is possible around resolving debt. When, via the Rolling Jubilee, we chanced upon a portfolio of private student debt from what was then one of the biggest for-profit colleges in the country (now defunct), Corinthian Colleges Inc., we knew we had found an opportunity to see if a more confrontational form of debtor organizing could work. For-profit colleges can be up to twice as expensive as Ivy League universities, and they are notorious for running afoul of the law by exploiting students for financial gain. When we bought the Corinthian portfolio, the company had been accused of fraud and predatory lending by everyone from Attorneys General to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, gaming the federal student loan system to the tune of $1.4 billion in federal grant and loan dollars in 2010 alone.

As Corinthian’s many scandals grew increasingly public in the summer of 2014, a small group of former students had already begun to organize. We began to work closely with a group of 15 former Corinthian students, as well as a group of technology experts and lawyers, who were ready to publicly declare their refusal to make any more payments on their federal student loans. In addition, we put together an online legal tool (via what was then a little-known provision in the Higher Education Act, known as Defense to Repayment) that allowed students all current and former Corinthian students to challenge their debts with the Department of Education, whether or not they could take the personal risk to join the strike.

In February of 2015, the Corinthian 15 went public with their history-making strike. Requests to join the strike poured in from current and former Corinthian students across the country. Rather than merely mark down all of the thousands who wanted to join, organizers made individual phone calls to all potential strikers, in an effort to make sure they understood the potential consequences of their act–a trashed credit score, wage garnishment, tax return garnishment, social security garnishment–phone call by phone call. Soon the strike had grown modestly to 200 debtors. Merely one year later ITT Technical Institute strikers have formed their own debtors union, our Defense to Repayment tool has been filled out over 10,000 times, and former Corinthian students have seen millions of dollars of debt relief in hard won battles with the Department of Education. Even in popular culture, there is good reason to believe this strike has started to change the terrain of possibility.

(From CBS’s “The Good Wife”, Season 7, Episode 5 – Payback)

Debtor organizing is complex, and the barriers to forming debtors unions are high. Unlike with many other types of unions, there are no shared factory floors. People in debt to the same institution are often geographically remote and disconnected from one another. Many debtors don’t know who profits when they pay their debts, or who stands to lose if they don’t. Yet the potential of our collective power as debtors is tremendous, and re-envisioning higher education—what it costs, who should pay for it—is only the beginning.

Imagine the power of mortgage-debtors’ unions to leverage eminent domain to halt foreclosures on individual homeowners, or criminal justice debtors-unions gumming up the works of the debt-to-prison pipelines from Ferguson to Los Angeles. Debtors unions can change the spaces of possibility across the unequal landscapes of contemporary capitalism. It will take persistent on-the-ground organizing—to help debtors see their common cause, challenge shared assumptions about what kinds of debt are legitimate, and take bold actions that disrupt the existing paradigm—to make such change possible.

Keep an eye on debtcollective.org for a new platform for collective debt resistance dropping in January 2017, and in the meantime, begin to talk to friends and family members about how we might rethink debt and credit for a new economic era. The question, as always, is, who owes what to whom?

- Last Week Tonight with John Oliver recently ran with this idea, without crediting our work or the work we did for his producer to make the segment.

Enough With Problem Solving, Let’s Start Creating

By Creativz

Could Basic Income Be a Game Changer for Artists?

By Alexis Frasz

Taking Note: Filling Gaps in Artist Data Knowledge

By Alexis Frasz

Debt: A System Failure, not an Individual One

By Ramona Gonzales

Creativity Connects: Trends and Conditions Affecting U.S. Artists

By Creativz

Online platforms are not enough. Artists need affordable space.

By Creativz

How does crowdfunding change the picture for artists?

By Creativz

Do artists have a competitive edge in the gig economy?

By Creativz

Can photographers restore their devastated business?

By Creativz

Who sets the agenda in America’s new urban core?

By Creativz

Artists, the original gig economy workers, have more rights than they think

By Creativz

Why we can’t achieve cultural equity by copying those in power

By Creativz

The art school of the future

By Creativz

What does it mean to sustain a career in the gig economy?

By Creativz

For profit or not, artists need tech designed for artists

By Creativz

Generosity as a guiding principle of life as an artist

By Creativz

Health insurance is still a work-in-progress for artists and performers

By Creativz

Want to be an artist? Be passionate and realistic about your career

By Creativz

Technology isn’t magic. Let’s make it work better for artists and musicians.

By Creativz

How artists and environmental activists both do better together

By Creativz

Introduction: What do artists need to thrive?

By Creativz

What artists actually need is an economy that works for everyone

By Creativz

Why arts funders and indie video game makers don’t click, and how to fix it

By Creativz

What is this?

CREATIVZ is a conversation about how artists in the United States live and work and what they need to sustain and strengthen their careers. It's part of a research project from the Center for Cultural Innovation and the National Endowment for the Arts, with additional support from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Surdna Foundation. Overall research and online strategy by Helicon. Online strategy and production by We Media.

Read more about the project.

Cover photo by Bill Dickinson via Flickr / Creative Commons